The Impact of the 1968 United Methodist Union on Mission

- May 16, 2018

- 5 min read

The United Methodist Church is celebrating the 50th anniversary of its founding, which occurred with the 1968 merger of the Methodist Church and the Evangelical United Brethren. Much of the celebration has been focused on the merger as an ecumenical achievement and a step forward in racial equality with the end of the segregated Central Jurisdiction of the Methodist Church.

This union also had significant implications for mission. Among these were effects on the global structure of the new denomination, increased attention to issues around racial justice, and new organizations that were formed for mission work, including the creation of United Methodist Women. While the Uniting Conference of 1968 was an important moment, the changes that took place spanned several years before and after the merger.

COSMOS and Autonomy Overseas

The Evangelical United Brethren and the Methodist Church brought to the merger different philosophies about mission work outside the United States. For the most part, the EUB sought to develop churches that would become autonomous and in most cases merge with missions from other denominations to form new ecumenical bodies. The Methodist Church sought, for the most part, to replicate throughout the world the structure of Annual Conferences that were directly related to the General Conference. Movements for independence in both political and church affairs in the 1960s, however, brought the Methodist Church’s assumptions and practices about mission into question. The 1964 General Conference charged the Commission on the Structure of Methodism Overseas (COSMOS) to “study the structure and supervision of the Methodist Church in its work outside the United States.” COSMOS’s extensive work explored not only the structure of the Methodist Church, but its relation to historically related denominations as well.

Its work in that quadrennium culminated in a consultation held at Green Lake, Wisconsin, in 1966. Leaders of the Methodist Church from throughout the world and leaders of the EUB participated. Attendees considered four possibilities for the future of Methodism outside the United States: 1) Keep the current central conference structure, 2) Promote autonomy among all national bodies, 3) Develop a global conference with regional general conferences, or 4) Grant autonomy, but allowing for substantial collaboration through some sort of world body. COSMOS’ report to the 1968 Uniting General Conference indicated that most participants were in favor of options 3) or 4), but given the impending merger with the EUB, COSMOS thought it would be "confusing" to bring a proposal to the 1968 General Conference. COSMOS did, however, put forward requests for General Conference to authorize autonomy for several branches of Methodism outside the United States, including Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Cuba, Pakistan, Peru, Singapore and Malaysia, and Uruguay. (Costa Rica and Panama were granted autonomy by the 1972 General Conference.) Although they requested autonomy for these annual conferences in 1968, COSMOS envisioned that these bodies would continue to be part of the discussions of a possible worldwide structure. In their eyes, becoming autonomous did not preclude a group from possibly being part of a larger structure.

Yet, such substantive changes in denominational structure were not to be. With the departure of the autonomous churches and the focus of much of the denomination on restructuring the boards and agencies (see below), the energy went out of the COSMOS process, and it recommended its own disbanding to the 1972 General Conference without ever bringing a proposal for structural changes. Keeping the current central conference structure became the default option. Interestingly, this path contrasts with sister denominations such as the Wesleyan Church (celebrating their own 50th anniversary this year) and the Free Methodist Church, both of which adopted self-governing bodies that remained in connection with the wider denomination.

Race Relations

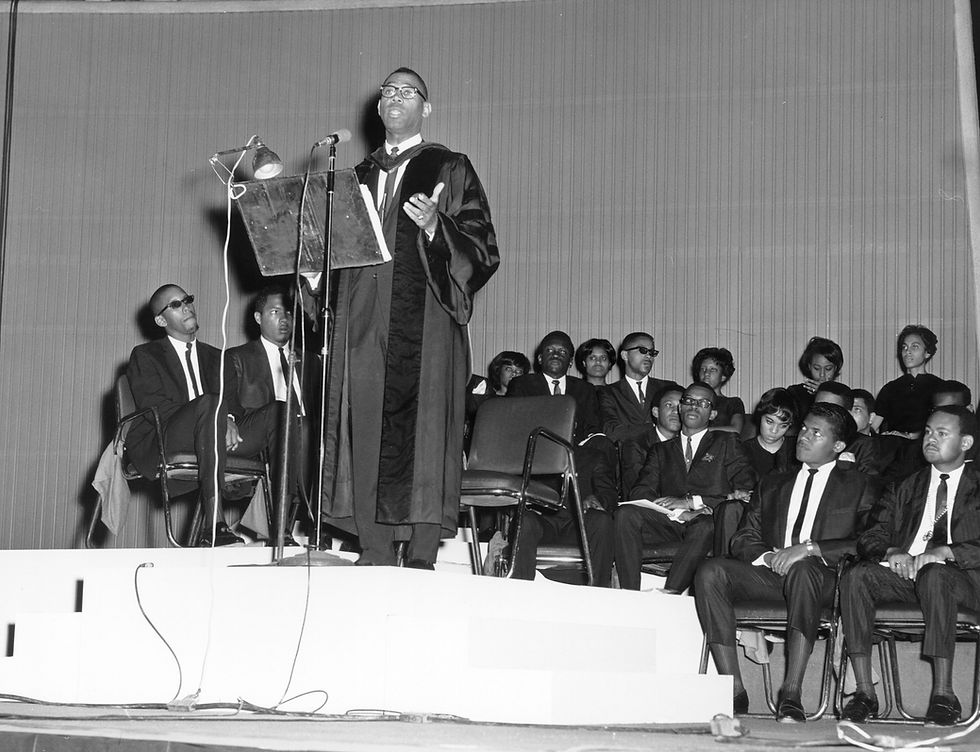

Challenges to control of mission by white North Americans came not only from the mission field, but also from African Americans within the United States. The newly formed Black Methodists for Church Renewal challenged the Board of Mission in 1969 to recall its missionaries from abroad and to deploy them to serve “the alienated poor in America.” This tied the anti-imperialist slogan “Missionary Go Home!” to the work of civil rights and anti-poverty activists in the United States. As the largest agency of the newly formed United Methodist Church, the Board of Missions served as a stand-in for African American frustrations with the denomination as a whole. Moreover, while the Women’s Division of the Board had conducted pioneering work in putting forward two Charters for Racial Equality, the rest of the Board was not seen as forward on race questions. There were no people of color in senior leadership positions. Black Methodists for Church Renewal were not the only ones who called on the Board to change its ways. The Black Economic Development Conference, led by James Forman, staged a sit-in at the Board’s offices in 1969, calling for reparations to African Americans. At the same time, black staff members formed a task force to call for further changes to the way the Board operated. Although it did not answer Forman’s call for $300 million in reparations, the Board generally accepted its staff’s recommendations. These recommendations led to $1.3 million in requested funding, the hiring of several senior-level black staff members, the start of the Community Developers Program, and greater attention to racial justice in training and educational materials. While these changes did not mark the end of racism in Methodist mission, they did represent a step forward and a model for advocacy directed at the Board that other minorities embraced in the following years.

Restructuring

Merging two denominations also meant merging two sets of denominational boards and agencies. The mission agencies of The Methodist Church and the EUB were similarly structured in three divisions—World, National, and Women’s. Yet that did not mean the process of combining the two denominations was easy! Indeed, restructuring boards and agencies was a major focus of denominational energies for the first four years of The United Methodist Church, culminating in a series of proposals adopted by the 1972 General Conference. Among other changes, the Board of Missions was renamed the General Board of Global Ministries. Women faced a particularly challenging path in the process of mission agency reorganization. Methodist women were still smarting from the effects of a 1964 reorganization of the Board of Missions. While that reorganization gave women more representation on the board, it deprived them of programmatic control over ministries that they supported financially and the authority to send out their own missionaries. Yet in the midst of this difficult situation, women in the new denomination laid the plans for the creation of United Methodist Women, which was founded in 1972. This organization would give new focus to and a long-term framework for women’s ministries in The United Methodist Church related to mission and spiritual development. United Methodist Women become an independent agency of the church in 2012.

Comments